The CPU: Your Code's Engine

Every line of code you write eventually becomes a series of simple instructions that a small piece of silicon executes billions of times per second. Understanding how this happens transforms how you think about performance.

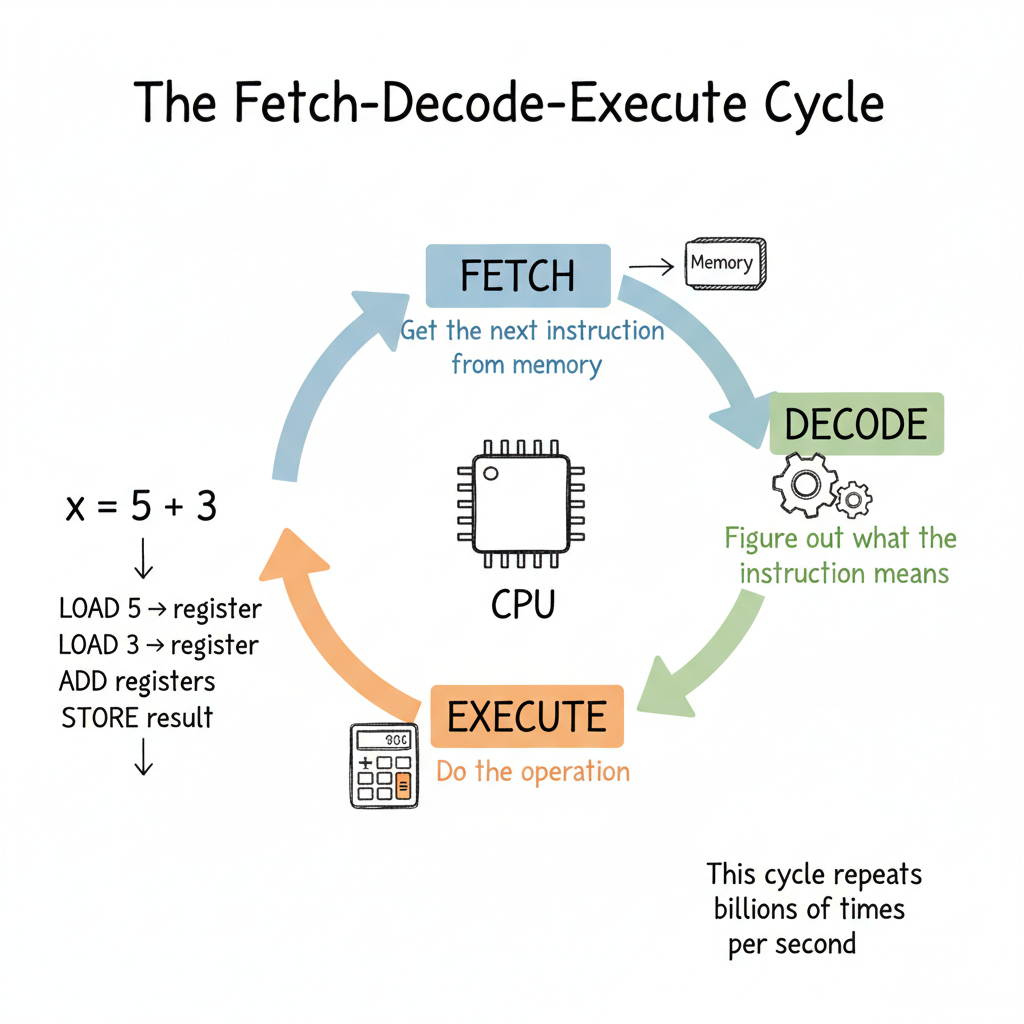

The Fetch-Decode-Execute Cycle

At its core, a CPU does one thing over and over:

- Fetch: Get the next instruction from memory

- Decode: Figure out what the instruction means

- Execute: Do the operation

That's it. This cycle repeats endlessly. A 3 GHz processor completes about 3 billion of these cycles every second.

Let's trace what happens when you run this simple code:

x = 5 + 3

Behind the scenes, this becomes multiple CPU instructions:

- LOAD the value 5 into a register

- LOAD the value 3 into another register

- ADD the two registers, store result in a third register

- STORE the result back to memory (the variable

x)

Each of these instructions goes through fetch-decode-execute. What looks like one line of code is actually many CPU operations.

Registers: The Fastest Storage You've Never Seen

You've heard of RAM. You might know about CPU cache. But the fastest storage in your computer is something most developers never think about: registers.

Registers are tiny storage locations inside the CPU itself. A typical CPU has:

- 16-32 general-purpose registers

- Each holds 64 bits (8 bytes) on modern systems

- Access time: less than 1 nanosecond

Compare this to:

| Storage | Access Time | Relative Speed |

|---|---|---|

| Registers | <1 ns | 1x (baseline) |

| L1 Cache | ~1 ns | ~1x |

| L2 Cache | ~4 ns | ~4x slower |

| L3 Cache | ~10 ns | ~10x slower |

| RAM | ~100 ns | ~100x slower |

When the CPU adds two numbers, it doesn't work with RAM directly. It loads values into registers, operates on them there, then writes results back. This is why compilers spend enormous effort deciding what to keep in registers.

Why This Matters to You

When you write a tight loop that processes millions of items, the compiler tries to keep frequently-used variables in registers. If there are too many variables, some get "spilled" to memory. This is measurably slower.

# This loop has few variables - compiler can keep them in registers

for i in range(1000000):

total += values[i]

# This has many variables - some may spill to memory

for i in range(1000000):

a = values[i]

b = other[i]

c = a * b

d = c + offset

e = d / scale

# ... more variables

You don't need to count registers manually. But understanding that they exist explains why simpler code often runs faster.

Clock Speed: What 3 GHz Actually Means

When you see "3.5 GHz processor," that means the CPU's internal clock ticks 3.5 billion times per second. Each tick is a cycle.

But here's the thing: one instruction doesn't always equal one cycle.

- Simple operations (ADD, compare) might take 1 cycle

- More complex operations (multiply) might take 3-4 cycles

- Division can take 10-20 cycles

- Memory access can stall for hundreds of cycles

This is why two CPUs with the same clock speed can have different performance. Instructions per cycle (IPC) matters as much as clock speed.

The End of the Megahertz Myth

In the early 2000s, CPU makers hit a wall. Higher clock speeds meant:

- More heat (power increases with frequency squared)

- More power consumption

- Physical limits of silicon

The solution? Stop making CPUs faster. Make more of them.

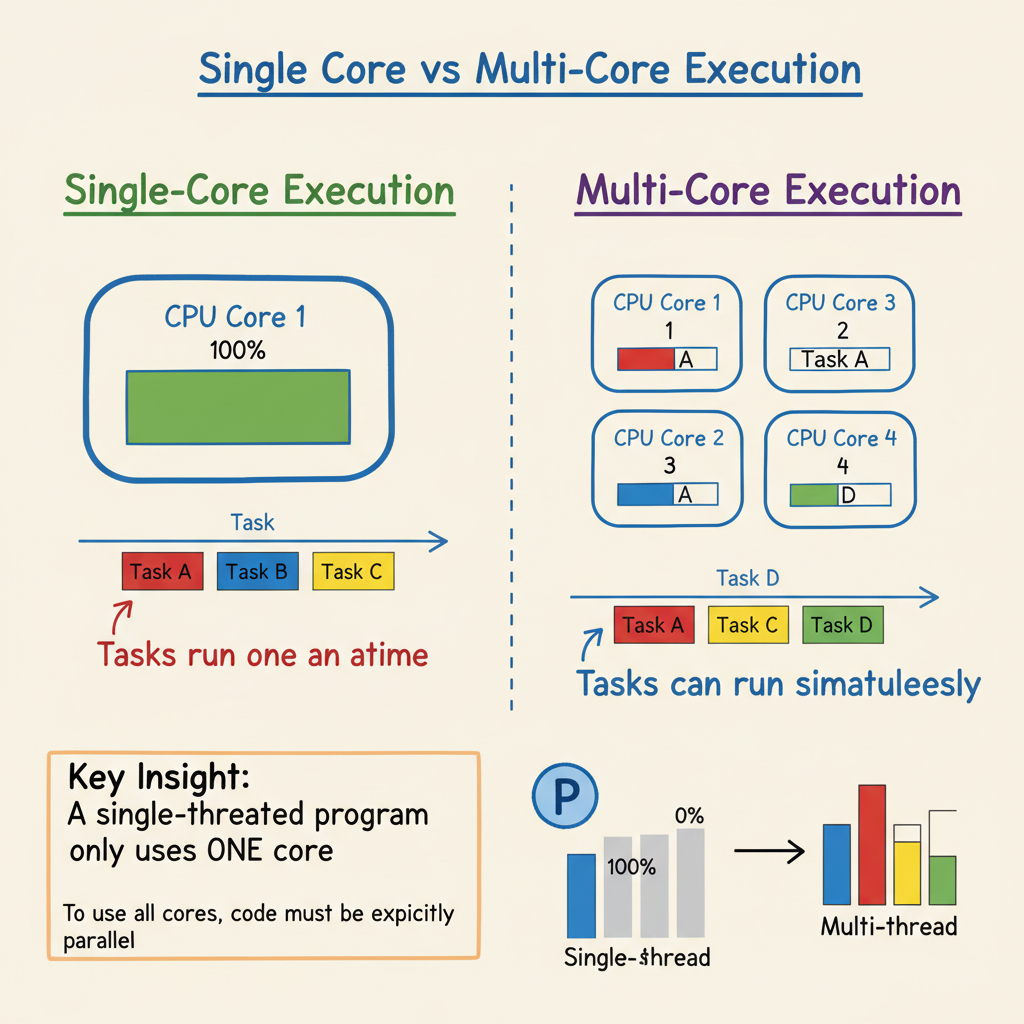

Multi-Core: Parallel Worlds

Modern CPUs have multiple cores - essentially multiple CPUs on one chip. Your laptop probably has 4-16 cores.

Each core can run its own fetch-decode-execute cycle independently. This means:

- Core 1 might run your web browser

- Core 2 might run your IDE

- Core 3 might run your build process

- Core 4 might handle system tasks

But here's the catch: a single program doesn't automatically use multiple cores.

# This runs on ONE core, no matter how many you have

for i in range(10000000):

result += expensive_calculation(i)

To use multiple cores, your code must be explicitly parallel:

# This can use multiple cores

from multiprocessing import Pool

with Pool(4) as p:

results = p.map(expensive_calculation, range(10000000))

This is why a program can peg one core at 100% while your "8-core" CPU shows only 12% total usage. One core is maxed out; seven are idle.

Pipelining: The Assembly Line Inside Your CPU

Modern CPUs don't actually finish one instruction before starting the next. They use pipelining - working on multiple instructions at different stages simultaneously.

Think of it like an assembly line:

- Position 1: Fetching instruction A

- Position 2: Decoding instruction B (which was fetched earlier)

- Position 3: Executing instruction C (decoded earlier)

This keeps all parts of the CPU busy. A CPU might have 14-20 pipeline stages.

When Pipelines Break: Branch Prediction

There's a problem. What if instruction B is:

if x > 0:

do_something()

else:

do_other_thing()

The CPU has already started fetching and decoding the next instructions. But which ones? It doesn't know yet whether x > 0.

The solution: branch prediction. The CPU guesses which branch you'll take based on history. Modern CPUs guess correctly over 95% of the time.

When they guess wrong, the pipeline must be flushed and restarted. This pipeline stall wastes 10-20 cycles.

This is why:

# Predictable branches - fast

for item in sorted_items:

if item > threshold: # All True, then all False

process(item)

# Unpredictable branches - slower

for item in random_items:

if item > threshold: # Random True/False

process(item)

Sorted data often processes faster than random data, even for the same operations, because the CPU predicts branches correctly.

Instruction Set Architecture: The CPU's Vocabulary

Different CPUs understand different instructions. This is called the Instruction Set Architecture (ISA).

x86/x64: Intel and AMD desktop/laptop chips

- Complex instructions that do a lot per instruction

- Backward compatible to the 1970s

- Powers most PCs and servers

ARM: Mobile devices, Apple Silicon, embedded systems

- Simpler instructions that are more efficient

- Lower power consumption

- Powers phones, tablets, and now high-end laptops

When you compile code, the compiler translates your high-level language into the specific instruction set of your target CPU. This is why you can't take a program compiled for an Intel Mac and run it on an M1 Mac without translation (like Rosetta 2).

Putting It All Together

Here's what happens when you run a Python script:

- Python interpreter (itself a compiled program) starts executing

- Your code is parsed into Python bytecode

- The interpreter's C code runs, processing bytecode

- Each Python operation becomes many CPU instructions

- Those instructions flow through the pipeline

- The CPU predicts branches, manages registers, coordinates caches

- Results flow back through the memory hierarchy

All of this happens billions of times per second.

The Insight

The CPU is not magic. It's a machine that does simple things very, very fast. Understanding its basic operations - fetch-decode-execute, registers, pipelining, branch prediction - helps you understand why some code runs faster than others.

When someone says "this algorithm is CPU-bound," you now know what that means: the bottleneck is how fast the CPU can execute instructions, not how fast it can fetch data from memory or disk.

Self-Check

Before moving on, make sure you can answer:

- What are the three steps of the CPU's fundamental cycle?

- Why are registers faster than RAM?

- Why doesn't doubling your cores double your program's speed?

- What happens when the CPU mispredicts a branch?

- Why might sorted data process faster than random data?